Three years ago Frank-Anders Thoresen’s phone rang at home in Minnesund, north of the Norwegian capital Oslo. It was his childhood friend Willy Itomo. This conversation led to Frank-Anders starting up a sawmill in Congo.

Frank-Anders grew up in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. His parents were missionaries in Bondo in the northern part of the country. The province of Bas-Uele is the forgotten part of Congo, far away from the unrest in the east of Congo, which is virtually the only thing that is reported in Europe.

”Bondo is almost 2,000 kilometers away from the troubles in Sud-Kivu,” explains Lasse.

Contact via mobile phone

Bondo is also forgotten when it comes to communications and other infrastructure. The area can only be reached quickly by hiring a private jet. The alternative is to walk, cycle or travel by motorcycle the 535 kilometers from Kisangani through the jungle.

But two modern inventions have found their way to Bondo: The mobile phone and the internet. When Willy Itomo got access to a mobile phone he called his childhood friend in Norway.

”Willy is a trained agriculturist and worked on a forest project in Bondo. One of the things they did was saw wood by hand,” says Frank-Anders.

The conversation resulted in Frank-Anders promising to join the project and provide some modern equipment.

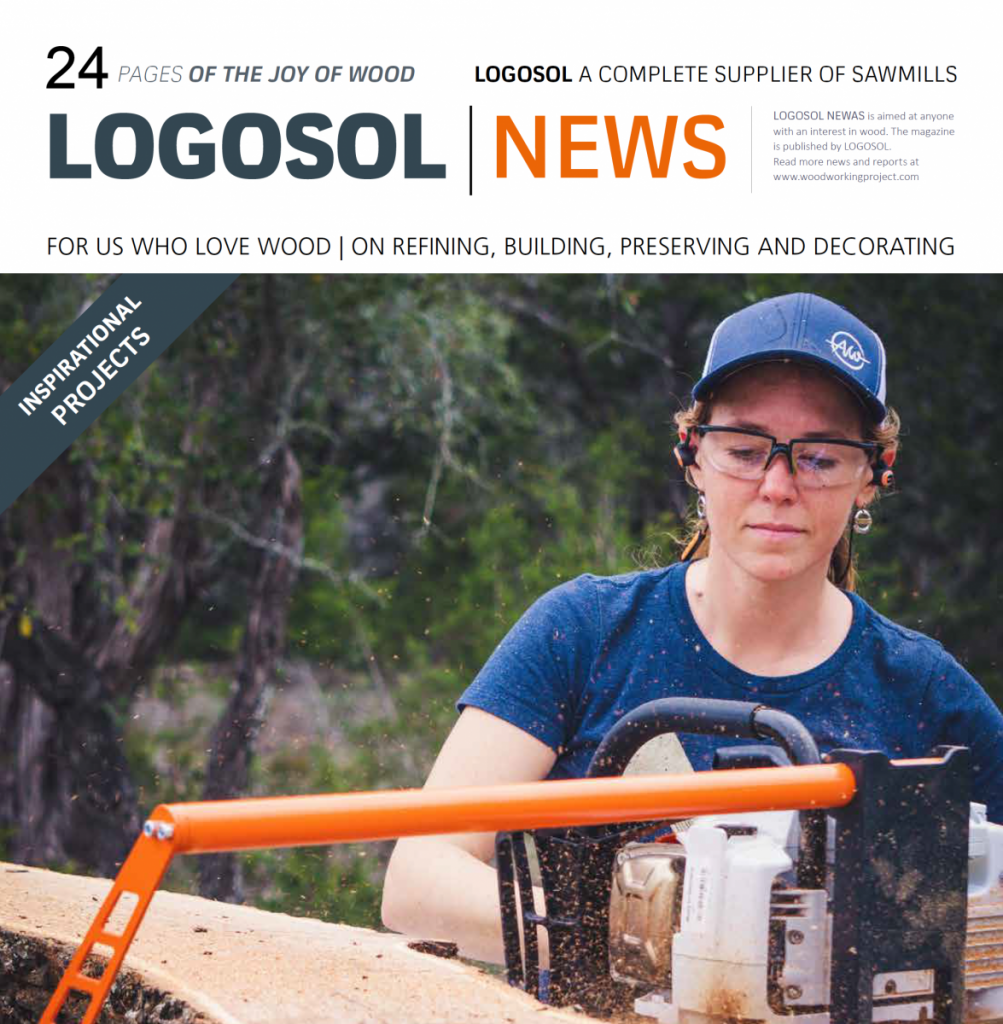

He decided that the best alternative was Logosol’s Big Mill LSG sawmill. He ordered two of these plus some other equipment that is impossible to buy in Congo. The chainsaws, which are a large model not found in Scandinavia, were bought in Congo.

Spare parts are the problem

Frank-Anders flew to Congo with 76 kg of baggage. That meant he was carrying an extra 26 kg over the weight limit. From the capital Kinshasa he flew onto Kisangani where Willy and some friends were waiting with motorcycles.

”We drove for 49 hours over three days to get to Bondo, with 70 kg of baggage on my motorcycle,” says Frank-Anders, showing photographs from the dangerous journey that featured broken-down motorcycles needing extensive repairs in the middle of the jungle.

The sawmills they took with them were put into production immediately.

”The Logosol LSG works perfectly. It’s small enough that it can be transported to the work site by motorcycle and big enough to cope with thick trees,” says Frank-Anders.

The biggest problem is getting hold of spare parts and fuel for the chainsaw, and for the tractor that the small company owns to transport the sawn wood. As far as the fuel is concerned, there is a method of transportation in use. Bicycle from Kisangani. People pedal through the jungle with 120 liters of fuel balanced on every bicycle. Spare parts on the other hand are virtually impossible to get hold of. More often than not, whatever does finally arrive is the wrong thing.

Local need for wood

Today the sawmill provides employment for four people. They produce up to 3 cubic meters of timber per day, mainly from the iroko and sapeli trees, the latter is also called mahogany. The timber is supplied exclusively to the local market.

Customers are a Catholic mission, two hospitals, schools, a home for disabled people, and the population of Bondo. It’s not even worth thinking about exports.

Partly because it would be too costly to do so and partly, according to Frank-Anders and Willy, because Congo’s raw materials should first and foremost benefit the country.

”There is an enormous need for wood. By only operating on the local and regional

market and using small-scale technology, we can fell trees in a responsible way that

doesn’t damage the environment,” says Frank-Anders.

The town of Bondo has a population of about 20,000 while around 200,000 people live in the area as a whole.

The project was originally financed by Frank-Anders and his parents. Sponsors are needed during the start-up phase to build up production operations that function well. The objective is for the sawmill to be self-financing and make a profit that can then be reinvested in Bondo. Frank-Anders is planning on working six months of the year in Congo.